Chapters

Battle of Cynoscephalae (197 BCE) was the decisive clash between Rome and Macedonia in the Second Macedonian War.

Background of events

Macedonia became Rome’s enemy in 215 BCE after siding with Carthage during the Second Punic War. Macedonia counted on spoils and territorial benefits, and to this end sparked the First Macedonian War (215-205 BCE). This conflict, however, did not bring about certain solutions. Carthage, after losing the war with Rome, ceased to play the role of dominos in the Mediterranean Sea. In turn, Rome, remembering the disgraceful action of Macedonia against the “eternal city”, during the defeats in Italy, decided to pay back its rival in Greece and gain the position of hegemon in these areas. All he needed was a good reason.

The war, later known as the Second Macedonian, began in 200 BCE when Attalos, King of Pergamonasked Rome to help fight Macedonia. It was the perfect opportunity for Rome to intervene in Greece’s internal affairs. Soon Roman troops entered the Peloponnesian Peninsula from Illyria, and some of them were transported by sea to Athens. The Greeks hated King Philip V and wanted to shake off his yoke, but only some of them openly supported the Romans. The Aetolian and Achaean League entered into an alliance with the republic and sent their troops against the Macedonians. Both sides of the conflict had similar forces and no one gained an advantage during the conflict. The situation changed in 198 BCE, when Titus Quinctius Flaminius, a young and able commander, became the leader of the Roman forces in this campaign. His actions and manoeuvres forced Philip to fight a major battle. The Macedonian ruler knew that, unlike the Romans, he had almost no reserves and his only chance was to defeat the enemy in a decisive clash. The battle took place in the hills of Cynoscephalae (the Greek words Kynos kephalai mean “dog heads”) near Larisa in May 197 BCE. enemy (although both chiefs were aware that the enemy was nearby). Philip V sent many soldiers with the task of getting food.

Military

The Roman army was led by Titus Quinctius Flamininus. The force (according to Plutarch) was approximately 33,400 soldiers. They were based on two legions, which, together with the contingents of Italian allies, numbered about 22,000 armed men. In addition, there were lightfoot soldiers: 6,000 (or 600, both of which are found in ancient sources) Ethols, 1,200 Athamans, and 800 Cretans (the latter were mercenaries sent by Sparta). The Roman cavalry consisted of 2,500 horsemen (including 400 Etols and perhaps 1,200 Numidians from Africa). These forces were complemented by a dozen or so elephants sent by the ruler of Numidia Masinissa and Carthage.

The Macedonian army was commanded by Philip V with a force of 25,500 soldiers, including 16,000 armed with long 7-meter long sarissa spears, and phalanxes. In addition, his army consisted of 2,000 peltasts, 5,500 other light-armed (mainly Illyrians and Thracians) and 2,000 cavalries (Thessalians and Macedonians).

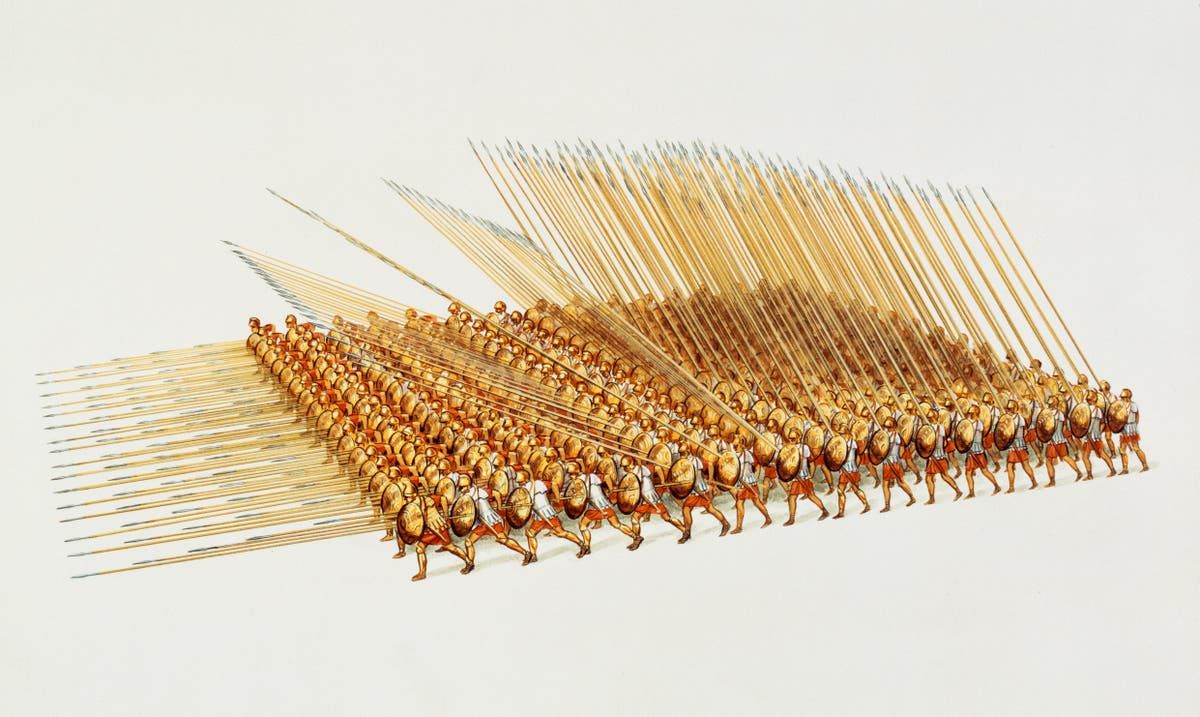

The phalanxes attacking the enemy did not run, so as not to confuse the formation, but marched at a steady pace. As they approached the enemy lines, they gradually tightened in formation. It was compact, but the soldiers did not quite stand shoulder to shoulder, there must have been gaps between them, through which those in the further ranks would put their spears forward. The advancing phalanxes raised the Macedonian battle cry: “Alalalai!”. After the collision with the enemy, the first ranks fought, which could reach him with sarisses. However, the rear ones did not stand idle. If a soldier fell dead or wounded, the one standing behind him would immediately take his place, so that the array did not lose its compactness.

Battle

The battle began with a random clash of 1,300 scout troops sent to the hills on the Roman side and around 2,000 on the Macedonian side. The Macedonians won the first clash, but Flamininus sent 2,500 Romans and Ethols to fight. Pushed from the hills, Macedonians sent messengers to help, and soon about 4-5,000 cavalry and light infantry arrived, forcing the Romans to leave the hilltops again. Seeing this, Flamininus understood that the entire Macedonian army was standing behind the hills and ordered the rest of his troops to be put into battle. Meanwhile, the commanders of the Macedonians fighting on the hills sent messengers to the king with the information that the enemy was retreating and a decisive blow should be struck. Philip V ordered his most powerful formation – phalanx (Macedonian phalanxes called themselves sarissoforoi).

As the sarissoforoi (“sariss-bearers”) formed lines, on the other side of the hills, Flamininus led his left-wing into battle – at least 12,000 men, mostly heavy legionaries. The Macedonians who were victorious in the hills were unable to withstand the impact and began to withdraw. Suddenly the Romans saw a forest of long Macedonian spears looming before them. It was the right-wing of the phalanx, which Philip led to the hills, although the left-wing was not ready yet (some of the soldiers sent for food only returned to the camp). When Philip saw the Romans advancing, he decided not to wait for the left-wing led by Nikanor. He developed a combat formation and fell on Flamininus’ troops, which had already prepared for the battle with the heavy infantry of the Macedonian king. Charging from above, armed with long spears – sarissas – Macedonians began to push the left-wing of the Romans, who were unable to break through the thicket of spears.

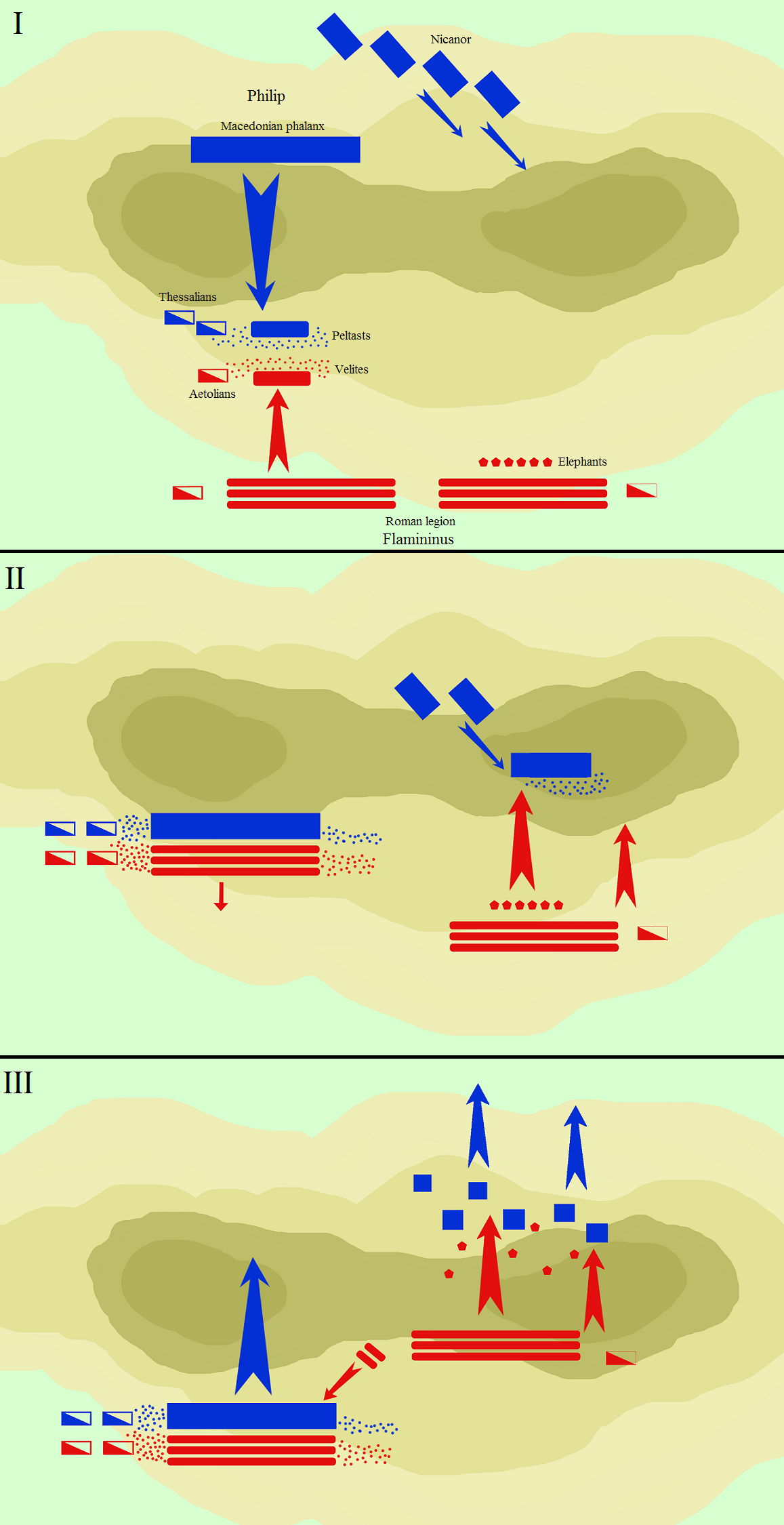

I. The Macedonian right wing is attacking the Romans left-wing, the rest of the main Macedonian forces are just climbing the hills.

II. The right-wing of the Macedonians pushes down the left-wing of the Romans, the rest of the Roman army attacks the scattered troops of the left-wing of the Macedonians.

III. The Romans break up the left-wing of the Macedonians, some 2,000 legionaries turn back and attack the rest of the Macedonian army from the rear.

Seeing this, Flamininus realized that he could not stop the royal phalanx. So he went to the right-wing of his troops, which had not yet participated in the fight. It had 16,000 Romans and Ethols (assuming that 6,000 Ethol foot soldiers took part in the battle), supported by a dozen or so elephants. Flamininus directed them to the left-wing of Macedonians, still not ready for battle (some of his soldiers were just climbing the hills, some were standing on them, and the rest were trying to catch up with the royal phalanx). The powerful blow wiped out single units of phalanxes, cavalry and light-armed men. The scattered left wing of the Macedonian army began to retreat, and the Romans and Etols followed. Thus, the battle broke up into two separate clashes. On his right-wing, Philip pushed the left-wing of the Romans, and Flamininus on the Roman right chased the left-wing of the Macedonians.

The result of the battle was decided by an anonymous tribune. Seeing that victory was doomed on the Roman right wing, he freed about two thousand legionaries from it and, turning back, climbed the hill again behind the royal phalanx on the Macedonian right wing, hitting it from behind. Surprised sarissoforoi from the rear ranks of the phalanx did not manage to turn back to receive the legionaries with sariss blades, less armed and armoured than the Roman infantry (apart from the sarissa, they only had a short sword and a small shield), they had no chance of effective hand-to-hand combat with the enemy attacking from behind. The phalanx broke up almost immediately. The phalanxes massively raised their 7-meter-long sarissas as a sign of surrender, the Romans who did not understand this sign cut them further, and as a result, there was a complete pogrom of the Macedonian right wing. Philip retreated with a few horses up the hill and, seeing defeat on both wings, left the battlefield with a handful of Macedonian and Thracian horsemen.

Consequences

Polybius and Livius agree that about 8,000 Macedonians died and 5,000 were taken prisoner. Livy recalls that one of the sources indicated huge losses of Macedonians, reaching even 32,000 dead, but such statistics can be approached with great scepticism. About 2,000 soldiers were killed or wounded on the Roman side. Flamininus announced that the Greek states previously under Macedonian rule were free. This event was then announced for the liberation of Greece and its release from the hands of the hated tyrant. King Philip V was forced to pay 1000 talents in silver, disband his fleet, most of the army, and send his son to Rome as a hostage.

The Battle of Cynoscephalae was the biggest defeat of the Macedonian phalanx in the history of ancient wars, next to the defeat at Pydna (re-assigned to Macedonia by the Romans). With the aforementioned Battle of Pydna and the disaster of the Seleucid army in the Battle of the Romans at Magnesia, she proved the legion’s superiority over the phalanx, revealing its imperfections – sensitivity to flank and rear attacks and the difficulty of maintaining its formation in uneven terrain. Numerous countries of the Mediterranean basin, so far using the phalanx (widely recognized from the time of Alexander’s conquests as the best type of foot troops) began to try to create formations modelled on the Roman legion. This was especially true of the Seleucid state and Egypt. However, this did not have a major impact on the political and military situation in the international arena of the 2nd century BCE and did not prevent the conquest of these countries by Rome. The “Eternal City” conquered Greece finally in 146 BCE.